Carpets Behind the Throne: Weaving Authority into History

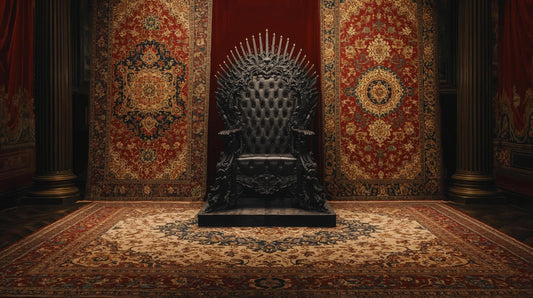

For centuries, handwoven carpets have done more than just cover floors – they set the stage for power. Imagine a Sultan receiving an envoy, a Shah signing a treaty, or an emperor holding court: in all these ceremonies, sumptuous carpets underfoot or behind the throne added gravitas to the moment. In fact, historical records show that court carpets were prized as symbols of status and wealth, laid out in reception halls and audience chambers of palaces.. They were even exchanged as diplomatic gifts – “ambassadors of cultural supremacy” – long before formal negotiations began. In other words, the carpet quite literally preceded the diplomat, speaking “more eloquently than any envoy” as it showcased a ruler’s prestige.

China: Dragons and the Throne Carpet

In imperial China, carpets were integral to court life. Japanese photographers in 1901 found the entire Forbidden City “wrapped in carpets,” most cut to fit palace halls and bear the chill of northern winters. Famously, the Ming emperors sat atop a dragon–pearl carpet. One 16th-century carpet (only one of 16 complete examples known today) shows twin five-clawed dragons chasing a flaming pearl, with the emperor’s throne placed squarely at its center. This was no mere decoration: dragons had been royal emblems for millennia, embodying the Chinese emperor as the “Son of Heaven,” and the pearl symbolized perfection and prosperity. As one historian notes, placing the throne in the middle of this red and gold dragon carpet visually asserted the emperor’s cosmic authority. In short, every color and motif on the carpet projected the ruler’s divine mandate, making even the floor beneath him part of the imperial ceremony.

In smaller council settings, carpets and mats also defined status. Footmen or ministers would sit or stand on the same luxurious ground as the monarch, reinforcing hierarchy. A camerawork from Ming paintings (and later Qing) often shows officials either standing or kneeling on richly patterned rugs during audiences, underscoring both ritual order and the sovereign’s supremacy. The presence of these carpets – in deep imperial reds, gilded embroidery, and powerful motifs – set an ambiance that announced who held power in the room.

Persia and India: Paradise Underfoot

In Safavid Persia and the Mughal courts of India, the “garden carpet” was a royal canvas. Safavid shahs of 16th–18th century Iran commissioned enormous silk carpets with paradise-like scenes. One surviving mid-16th-century Safavid court carpet is entirely silk, its field teeming with wild animals (lions, rams) and luxuriant florals – a living tableau of a king’s domain.Carpets for religious or state use often featured majestic medallions and scrolling vines, each symbolizing cosmic order and divine favor. Persian poem-makers even compared royal lions on carpets to celestial constellations, underlining that a king’s rug rivaled the heavens in honor.

Safavid workshops also wove the famous Ardabil Carpet (1539–40), now in London, whose symmetrical rosette medallions and pair motifs evoke a stylized garden or “paradise carpet.” (Its exact role is debated, but its artistry surely reflected royal taste.) Mughal emperors, drawing on Persian and Turkic heritage, similarly used carpets in court and ceremony. Early Mughal emperors employed Persian artisans, so their rugs carried Safavid or Timurid designs. Later, richly patterned botanical carpets adorned imperial tents and thrones, echoing the Mughal love of naturalistic floral art (see Flowers Underfoot: Indian Carpets of the Mughal Era, Met Museum).

In daily council ritual, Safavid manuscripts show the king seated on a carpeted platform in a pavilion, advising nobles or entertaining foreign dignitaries. Even outdoors, carpets marked special seats – spreading a prized rug on the ground signaled that a ruler was hosting an important court or celebration. Thus in Persia and India, the ground itself became symbolic – a built-in stage where the shah or emperor was visually at the center of a paradisal design, projecting bounty and divine right.

The Ottoman Sultan’s Palaces

The Ottoman sultans of Istanbul likewise lavished carpets in their palaces and councils. From the 16th century onward, Topkapı Palace and other court complexes were festooned with Anatolian rugs. Wealthy court patrons used designs (like the famous Uşak medallion) to carpet audience halls and even outdoor pavilions. In a classic 16th-c. miniature, Sultan Murad III receives a Safavid envoy seated before a massive red-and-blue Uşak carpet. The painting tells the story: the carpet serves as a plush backdrop to the ceremony, signaling Ottoman prosperity and power to the visiting dignitary. As Smarthistory explains, such court carpets were “ornate works of art that indicated the status and wealth of their owners,” used in reception halls, audience chambers, and even mosques sponsored by the palace.

Notably, even how carpets were placed in Ottoman and Persian courts was regulated. In Topkapı, for example, only the Sultan’s private chambers held the finest Uşak rugs – ordinary courtiers could never tread on them. (Similarly in Europe, early English inventories note that Tudor kings placed cherished Persian rugs atop tables “too precious for feet” Ottoman courtiers also used carpets to mark protocol: layered rugs could guide guests from outer to inner rooms, and a visitor’s rank was often shown by the number or position of carpets before him. In short, the sultan’s marshals literally rolled out carpets to map who stood where.

Europe’s Salons and Ambassadors

In Renaissance and Baroque Europe, imported Oriental carpets became a favorite status symbol in courts. When Persian Shah Abbas I sent “magnificent silk and metal-thread carpets” to Venice’s Doge’s Palace in the 1500s, he wasn’t just gifting furniture – he was dispatching “ambassadors of Persian cultural supremacy”. European kings took note. By the 17th century, Louis XIV even founded France’s Savonnerie carpet workshop to rival the opulence of Persian carpets. His designers wove vast carpets for Versailles and the Louvre that proclaimed French glory: as Louis famously ordered, “When foreign dignitaries cross our thresholds, they should know immediately they walk upon the glory of France”.

European royal portraiture testifies to how carpets conveyed power. Hans Holbein’s portrait of Henry VIII (1537) famously shows the king striding across a bold Anatolian carpet. Contemporary courtiers remarked that “the pattern beneath the feet steadies the throne”. In other words, the geometric medallions and repeating designs visually reinforced royal stability. Spain’s Philip IV sat before a Cuenca wool carpet in Velázquez’s portrait, the dynamic diagonal design cutting a path under the king’s feet (an image of conquest and order). And English Stuarts often displayed prized Persian carpets on furniture or walls, keeping them out of reach to underline their preciousness.

Across Europe, courts and councils were often carpeted in imported rugs. In Ottoman-influenced Vienna or Hungary, even local palaces imitated Turkish style: one wrote that entering an Eastern European throne room felt like crossing “the threshold of Ottoman majesty,” thanks to the big Ushak rugs on the floor. By the 18th century, the metaphor of the “red carpet” at formal events (parliaments, coronations, gala entrances) had emerged from this older tradition of using special carpets for ceremony.

Symbolism & Design: Patterns of Power

Symbols woven into carpets carried clear messages of authority and order. In both East and West, lions and dragons were royal emblems. The lion – a Persian favorite – has signified strength, courage, and kingship since antiquityi. Iranica notes a “long tradition of spreading lion rugs in royal courts” as a “sign of power”. Likewise, the Chinese dragon motif on imperial rugs and robes underscored the emperor’s divine role.

• Dragons & Lions: Carpets for emperors often depicted fierce beasts. The Ming throne carpet’s five-clawed dragons chasing a pearl made clear this was the ruler’s carpet, symbolizing cosmic might. In Persian domains, lions prowled the field to invoke regal valor and the shah’s guardianship over his realm. Embroidered “lion-and-sun” emblems even appeared on Persian flags and thrones, reinforcing that the ruler was as majestic as the sunlit lion on the carpet.

• Floral & Medallion Motifs: Repeat patterns also spoke volumes. Safavid “paradise carpets” were filled with endless flowers, trees and sometimes paired animals – a stylized garden underfoot. Such designs conveyed abundance and divine favor: a ruler literally sat among symbols of celestial bounty. By contrast, strong geometric medallions and arabesques (common in Anatolian rugs and Western Savonnerie works) suggested order and balance. As noted, European kings and their courtiers saw the checkerboard or starred patterns as signifying a steady, reliable regime – again, “the pattern beneath the feet steadies the throne”.

• Color & Space: Rich reds, golds, and blues were chosen deliberately. A deep crimson ground (often dyed with costly safflower in Asia) signaled wealth and urgency – it literally caught the eye at court. In palace chambers, placing an intense-red carpet at the foot of the throne made the ruler pop out in stark contrast. Meanwhile, calming earth-tones or ivory fields with flowing botanicals would be used in reception rooms to put guests at ease. Interior designers today note that even now, a central rug with a bold medallion can anchor a room just as it did a throne room, while lighter, botanical rugs feel tranquil and inviting. In short, every weave and hue was part of the message: bold repeated geometry equaled dominance, and gentle swirling flora said “welcome” – an ambience subtly calibrated for the scene.

• Diplomatic Gesture: Finally, the act of gifting and laying out a carpet was itself loaded with meaning. In diplomatic exchanges, presenting a rare court carpet was like presenting a microcosm of the empire’s glory. Turkish and Persian sources recorded that arriving envoys were often led to stand on the Sultan’s finest rug – an honor, but also a demonstration of hospitality turned performance. As the rug dealer Rug & Kilim summarizes, “When foreign dignitaries cross our thresholds, they should know immediately they walk upon the glory of France”. In this way, carpets helped set the tone of any council: opulence and cultural pride ready to influence proceedings.

In practice, rulers and interior planners understood the psychology of space: a meeting held on fine carpets felt more momentous. A rumor had it that Napoleon insisted on a Persian rug under his desk during negotiations (if true, it matches the idea that the fabric of the floor carries significance). The takeaway is that pattern and placement worked together to project calm, legitimacy, or awe as needed.

Enduring Allure of Courtly Carpets

Today, the grand halls where many historic councils met have been refitted, but the legacy of those carpets endures. The same motifs – the medallion recurs, the arabesques bloom, the dragons and lions re-emerge – have crossed into modern taste. Interior designers prize these designs for the very reasons royal weavers did: they imbue a space with richness and narrative depth. Buyers and collectors feel a thrill inheriting that symbolism. Walking on an antique rug once meant walking in the footsteps of kings; now it means treading on art layered with history.

In short, yes – handwoven carpets have played roles in major political and royal settings. From Ottoman throne rooms to Persian courts to European palaces, the walls and floors were not the only players in power’s theater: the floor itself, by virtue of its carpet, often spoke. It set the scene for diplomacy, underlined authority through color and motif, and even whispered to courtiers that they walked on the glory of empires. The traditions they established still resonate: even today a carpet underfoot can transform a room’s mood, just as in ages past it marked who truly sat in command.

Key Takeaways for Design: Royal carpets were not mere décor but statements. Bold medallions or repeated geometric designs (often in rich reds and golds) were chosen to impress and stabilize authority, whereas delicate floral or arabesque patterns created a sense of paradise and calm. Symbolic images – like lions for kingship or dragons for divinity – were woven in for all to see. When carpet makers “sent ambassadors” of pattern to other courtsr, they harnessed this visual language of power. Modern enthusiasts and designers continue this legacy: the right rug underfoot still organizes a room’s energy, echoes tradition, and quietly declares who’s in charge of the space.

Sources:

3.4: Later period - Humanities LibreTexts

The Role of European and Persian Rugs in Royal Palaces and Historic Estates | Rug & Kilim

The Role of European and Persian Rugs in Royal Palaces and Historic Estates | Rug & Kilim

One of only 16 complete Ming dragon carpets known to exist | Christie's

One of only 16 complete Ming dragon carpets known to exist | Christie's

One of only 16 complete Ming dragon carpets known to exist | Christie's

3.4: Later period - Humanities LibreTexts

3.4: Later period - Humanities LibreTexts

3.4: Later period - Humanities LibreTexts

LION RUGS - Encyclopaedia Iranica

3.4: Later period - Humanities LibreTexts

The Role of European and Persian Rugs in Royal Palaces and Historic Estates | Rug & Kilim

The Role of European and Persian Rugs in Royal Palaces and Historic Estates | Rug & Kilim

The Role of European and Persian Rugs in Royal Palaces and Historic Estates | Rug & Kilim

The Role of European and Persian Rugs in Royal Palaces and Historic Estates | Rug & Kilim

The Role of European and Persian Rugs in Royal Palaces and Historic Estates | Rug & Kilim

LION RUGS - Encyclopaedia Iranica

LION RUGS - Encyclopaedia Iranica

The Role of European and Persian Rugs in Royal Palaces and Historic Estates | Rug & Kilim

No comments

0 comments