The Art and Craft of Ottoman Carpet Weaving

Carpet weaving flourished in the Ottoman Empire as both a folk craft and a court art, blending Anatolian traditions with Persian, Arab, and later European influences. Anatolian Turks brought a millennium-old pile-weaving heritage when they settled in Asia Minor in the 11th–13th centuries[1]. Under the Ottomans (c. 1299–1922) carpet-making became a major industry. By the 16th century, sultans and elite patrons established imperial workshops (like Topkapı Palace’s kilims) that created distinctive court designs. As Marika Sardar notes, Ottoman weaving “was transformed from a minor craft… into a statewide industry with patterns created in court workshops,” producing quantities of carpets traded across Europe and Asia[2]. Ottoman court carpets often wove together Asian and Egyptian techniques; for example, Sultan Murad III famously imported Egyptian wool and weavers to Istanbul in 1585, so that mid-16th/17th‑century Ottoman rugs mixed Cairene weaving methods with Istanbul design[3]. Over the next centuries the trade in “Turkish” carpets boomed – European merchants prized them as luxury items. From the 15th c. onward Ottoman rugs were exported to Europe, and by the Dutch Golden Age (17th c.) Ottoman carpets were used as conspicuous table and wall hangings among elites[4][2]. (Indeed, Hans Holbein’s and Lorenzo Lotto’s paintings helped popularize Turkish “Uşak” designs.) Internally, woven carpets served Sultan’s mosques, palaces, and pavilions, proclaiming Ottoman prestige. By the 18th–19th centuries, luxury carpets like those from Hereke or Uşak were state-sponsored items of diplomacy and gift-giving[5][6].

Weaving Techniques and Materials

Ottoman carpets were hand-knotted on looms much like other Islamic carpets, using tight double (Turkish/Ghiordes) knots on cotton or silk warps. (This Turkish symmetrical knot – in which each yarn is wrapped around two warp threads – makes the pile very durable[7].) After each row of knots, one or more weft strands were beaten down to secure the pile, resulting in a dense, soft carpet. Fine court carpets often used silk or high-twist wool and employed extra technique (e.g. double stitching) to increase knot density. In fact, Ottoman “court” rugs often used S-spun wool (a technique from Egypt) even when woven in Turkey – a legacy of the 1517 conquest of Egypt[8]. Lower-end or village carpets used ordinary wool on cotton warp/wefts. Natural vegetal dyes colored the wool – deep madder reds, indigo blues, rich golds and greens – although by the 19th c. some aniline dyes were adopted.

Materials varied by quality and region. Wool was the staple for pile, prized for warmth and availability; Ottoman looms also used cotton (usually for the foundation warp/weft) and silk in the finest pieces. In luxury works (especially court and 19th‑c. Hereke carpets), silk warps and sometimes silk pile were woven, often with metallic threads (gold or silver-wrapped) for highlights[9][10]. For example, Hereke carpets – woven in the 19th c. palace workshop – are famous for combining fine wool or silk yarn with shimmering gold or silver accents[9][10]. The careful double-knotting and high knot-per-inch counts of these imperial workshops created detailed pattern edges and long-lasting rugs[11][10].

Design Motifs and Symbolism

Ottoman carpet designs draw on both abstract geometry and stylized botanical art, often echoing contemporary painting, tilework and manuscript illumination. Two prominent “court” styles emerged in the 16th–17th centuries: Saz (leaf scroll) style and floral style. The saz style features long, sinuous arabesque leaves and vining scrolls, while the floral style shows more naturalistic tulips, hyacinths, roses and carnations[12]. Weavers freely combined both, along with the cintamani motif (a row of three spots flanked by wavy lines, sometimes called “tiger stripes”[13]). Palmettes (lotus flowers), rosettes, cloud-band curls, and star/rayed disks are also common elements. For example, a late-16th or 17th-century Ottoman court carpet in the Metropolitan Museum shows stylized lotus flowers, feathery leaves and tightly curled cloud-scrolls, reflecting the imperial design vocabulary[3]. (Such carpets used an asymmetrical knot and Egyptian wool even when designed in Istanbul[3].)

Prayer rugs deserve special mention. These smaller carpets (typically ~1–2 m long) are woven for ritual use and invariably include an architectural arch or mihrab motif at one end, symbolizing the doorway to paradise[14][15]. Often a mosque lamp is depicted hanging under the central arch, and minaret-like columns flank the niche. The arches themselves sometimes echo Byzantine or Andalusian column designs – in one court prayer rug (c.1575–90) slender paired columns under domes frame triple-arched niches, a motif imported from Spanish-Moorish art via exiled Jews[15][16]. These carpet motifs tie together sacred imagery (the mosque mihrab) and Ottoman floral symbols. Bright tulips, carnations, and blossoms often fill prayer rugs, evoking the Islamic paradise garden[15].

Geometric carpets (especially village or nomadic weavings) use repeating lobed medallions or polygonal gul motifs, often in ochres, blues and crimsons. For instance, Konya/Yörük rugs feature bold hexagonal and gul medallions (such as the “Memling gul”) with earthy yellow-terracotta palettes[17][18]. Likewise, Bergama and Karaman (Ladik) nomadic weavings use stepped diamonds and latch-hook motifs. Even figurative elements appear occasionally

Geometric carpets (especially village or nomadic weavings) use repeating lobed medallions or polygonal gul motifs, often in ochres, blues and crimsons. For instance, Konya/Yörük rugs feature bold hexagonal and gul medallions (such as the “Memling gul”) with earthy yellow-terracotta palettes[17][18]. Likewise, Bergama and Karaman (Ladik) nomadic weavings use stepped diamonds and latch-hook motifs. Even figurative elements appear occasionally – Ottoman carpets might include stylized birds or animals, though this is more typical of Persian influence.

Overall, carpet imagery often carries symbolic weight. Floral vines and paradise gardens illustrate themes of abundance, while the prayer-arch motif expressly symbolizes the gateway to paradise[15]. Even abstract elements had meaning: the repetitive “cintamani” tri-dots may allude to cosmic harmony, and geometric lozenges echo the ordered cosmos. Carpet borders frequently use palmette chains and vine scrolls that parallel contemporary tile and textile borders, tying carpets into the larger Ottoman decorative vocabulary[19][12].

Regional Weaving Centers

Different Anatolian regions developed distinctive carpet styles under Ottoman rule.

- Hereke (near Istanbul). Established by Sultan Abdülmecid I (r. 1839–61) as an imperial manufactory, Hereke produced the empire’s finest carpets[5][6]. Weavers imported the best artists, creating palace-size carpets (the Ambassador’s Hall carpet in Dolmabahçe is ~120 m²)[5]. Hereke designs combine classical Ottoman motifs with Persian-inspired curvilinear floral patterns[20][21]. They often use luxurious materials: wool-and-silk or pure silk grounds, plus gold/silver-wrapped yarns for highlights[9][10]. The double Ghiordes knot is used at very high density (often 30–60 knots/cm²) giving a supple weave[11][10]. Typical motifs include intricate rosettes, arabesque foliage, and sometimes stylized architectural elements (arches or palaces). After the 19th c., genuine royal Hereke rugs were almost never sold openly; even today “Hereke” denotes elite-quality hand-knotting with Ottoman patterns[5][10].

- Uşak (Western Anatolia). Uşak (Oushak) was a major rug center from the 15th century onward[22]. Early Ottoman Uşaks are famed for their large medallions and star motifs set in broad fields (e.g. the “Lotto” or “Holbein” carpets seen in Renaissance art). They typically use the Turkish knot on wool (sometimes cotton warps) and vibrant dyes. A first-half-17th-c. white-ground Uşak medallion carpet (Met collection) shows a central round medallion with leafy tendrils on a light field[23]. Uşak rugs are also known for their luminous wool and warm color palette (deep crimsons, saffron-gold, blues and greens)[24]. In later centuries (19th c.) Uşak weavers adapted Persian floral designs to larger “prayer-size” and room-size rugs to meet European tastes[25].

- Bergama (Kozak, Yuntdağ near İzmir). Bergama rugs are famous in art history (the “Holbein Type” carpets). Bergama workshop and village weavings often feature a central large medallion (or multiple medallions) and floral scrolls. Some classic Bergama designs (15th–16th c.) use geometric hooked motifs on a red field. The region also produced “double-niche” prayer rugs and saddle bags. Notably, Holbein painted imported Bergama weavings with quartered lobed medallions against red fields[26]. Village-made Bergama rugs can be grouped iconographically into a bold “Caucasian” look (blocky geometrics) and a “Turkish” floral type (curving vines and flowers)[27]. A typical Bergama pattern is a row of concentric octagonal or rhomboid medallions with latch-hook ornaments, a motif inherited from Yörük nomads[28].

- Konya (central Anatolia). The Konya/Greater Konya area was an ancient weaving center (Marco Polo praised its carpets as “most beautiful in the world” in 1292)[29]. Ottoman-era Konya carpets are prized for luxurious local wool and tribal geometric designs. Classic features include earth-tone backgrounds (yellows, terracottas) with dark brown or red wefts, and scattered hexagonal “gul” medallions[17][18]. Motifs are strongly tribal: hooked diamonds, stars, stylized flowers, and Memling guls. Konya rugs tend to be coarsely knotted and deeply dyed, reflecting nomadic roots. (Other central Anatolian styles like Karaman or Ladik have related motifs.)

Each of these regional styles kept the Turkish symmetric knot, distinguishing them from Persian (asymmetric) carpets[30][7]. In practice, Ottoman carpets blended influences: even Uşak or Bergama weavings might incorporate Persian floral detail after the 18th c., while Hereke designs consciously echoed Safavid motifs[20][10].

Economics and Trade

Ottoman carpets were both a domestic staple and a valuable export. Within the empire, weaving was often done in rural households (especially western Anatolia) as part of village economies[31]. By the 19th century, commercial centers like İzmir (Smyrna) became trade hubs. State-sponsored manufactories (like Izmit, Hereke, and Karabük) also emerged. Carpets were collected for the Sultan’s palaces and mosques (Topkapı, Süleymaniye, Dolmabahçe all housed grand carpets). At the same time, oriental carpet galleries in Istanbul and İzmir sold carpets to Europeans and Levantine merchants.

Exports boomed from the 15th c. onwards. European demand for “Turkish rugs” was substantial: Venetian, Dutch and later British merchants carried Ottoman carpets to Europe and the Americas. As noted above, by the 1600s Dutch patricians displayed them as luxury

home decor[4]. In the 18th–19th centuries, the global market shifted: Central Asian (Uzbek) and Persian rugs became popular again, but Turkish carpets still found customers. Research shows that in the late Ottoman period, European firms even opened design offices (for instance, English companies opened an İzmir design office) to influence Anatolian production for Western tastes[31]. By that time, some traditional color schemes and motifs were altered under foreign demand.

Ottoman carpet trade also influenced Anatolian weavers’ economy. The Textile Society of America notes that carpet-making remained a “home industry” for rural families until the 19th century[31], with women weaving on foot-pedal looms from memory of pattern “samplers” (örneklik). However, exposure to European markets led to product standardization. For example, Isparta (southwest Turkey) weavers in the late 19th c. began using pattern papers and synthetic dyes under foreign tutelage[32]. Carpets were often bartered for imports (coffee, fabrics, etc.) or sold in metropolitan bazaars. By the late 19th c., competition from British machine-made carpets (Wilton rugs) and cheaper imports eroded Ottoman exports. Still, carpets remained one of the empire’s notable manufactures, alongside silk and cotton textiles[2][4].

Cultural and Artistic Impact

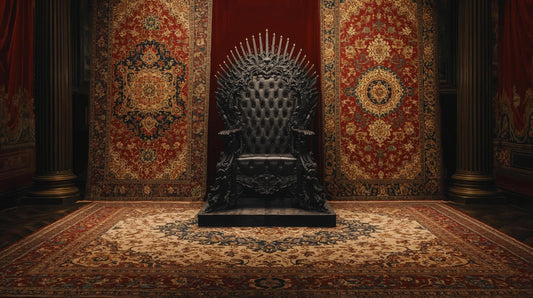

Ottoman carpets were integral to courtly and religious life. They furnished mosques (carpeting the floors of Süleymaniye, Selimiye, and other great mosques from the 16th century onward), palaces (Topkapı and Dolmabahçe sat atop miles of pile rugs), and fortresses. Carpets also hung on walls, served as canopies, or draped furniture – they were mobile works of art. Manuscript miniatures and travelogues often depict Ottoman sultans and nobles on carpeted divans. A painting of Sultan Murad III’s court, for instance, shows a red-and-blue Uşak carpet as a backdrop to a diplomatic audience, signaling imperial wealth[8].

Artistically, carpet motifs both reflected and influenced Ottoman design in other media. The court carpet workshops were closely linked to tile, ceramic, textile and manuscript workshops. Motifs like the saz leaf and tulip motif, developed by palace artists, appear on Iznik ceramics and book covers as well as on rugs[12]. The tripartite mihrab arch motif in prayer rugs echoes mosque architecture, and even migrates into wood-carved mihrabs and fountain niches. Indeed, the Met Museum observes that an imperial prayer rug with triple arches “exemplifies how Ottoman designs and motifs, originating in the court design workshop, were incorporated into religious as well as secular art”[33][15].

Internationally, Ottoman carpets became cultural symbols of the empire. European artists painted them in still lifes and religious scenes (Holbein’s Darmstadt Madonna famously features a Bergama carpet on the floor), and they were copied by western weavers (the Smyrna flatweave is named after Izmir/Uşak). Meanwhile, Ottoman taste was cosmopolitan: Persian and Caucasian carpets were also imported for the palace, and Ottoman carpets were sent as gifts to European monarchs. This exchange helped interlace Ottoman visual culture with that of neighbors. For example, as noted above, the paired-column motif in a late 16th-c. prayer rug came from Muslim exiles from Spain[34], showing how carpets could carry foreign architectural ideas into Ottoman design.

In sum, Ottoman carpets were much more than floor coverings. They were state-sponsored art pieces, peasant handicrafts, and international commodities all at once. Their weaving techniques and motifs synthesized centuries of Central Asian Turkic tradition with Persian, Arab, and European influences. Through their rich designs and fine materials, these carpets left an enduring mark on Ottoman art and on decorative arts worldwide.

Sources: Historical surveys and museum catalogues of Ottoman textiles[19][12][15]; specialized studies on Ottoman carpets and trade[3][4][5]; and encyclopedic articles on regional rugs[22][26][17][35]. These sources provide detailed descriptions of techniques, motifs, and the social role of carpets in the empire.

[1] [32] Carpet weaving in Isparta - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carpet_weaving_in_Isparta

[2] [19] [30] Carpets from the Islamic World, 1600–1800 - The Metropolitan Museum of Art

https://www.metmuseum.org/essays/carpets-from-the-islamic-world-1600-1800

[3] Ottoman Court Carpet - The Metropolitan Museum of Art

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/450466

[4] dutchculture.nl

[5] [21] What are Hereke carpets? [Sati Rugs | Hand-woven carpet specialty store]

[6] [10] [35] Hereke carpet - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hereke_carpet

[7] Ultimate Guide to Turkish Rugs | Biev

[8] [12] [13] [14] 3.4: Later period - Humanities LibreTexts

[9] [11] [20] Hereke Rugs | Fine Antique Turkish Carpets by Nazmiyal Collection

https://nazmiyalantiquerugs.com/hereke-rugs/

[15] [16] [33] [34] Image 24 | The Metropolitan Museum of Art

[17] [18] [29] Konya carpets - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Konya_carpets

[22] [24] [25] Ushak carpet - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ushak_carpet

[23] Ushak Medallion Carpet on White Ground - The Metropolitan Museum of Art

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/453237

[26] [27] [28] Bergama carpet - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bergama_carpet

[31] "West Anatolian Carpet Designs: The Effect of Carpet Trade between Ott" by Elvan Anmac and Filiz Adigüzel Toprak

https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/436/

No comments

0 comments